By Elliott Kalb

![]()

![]()

Ranking: ![]()

![]()

![]()

When I got this book, my expectations weren't too high, I was pleasantly surprised.

Kalb lists his methods for ranking players in the introduction, using measuring sticks such as MVPs, Championships, All-Star appearances, first and second-team All-NBA honors, outside opinions, and to break ties, he takes big over small, new over old, and winners over losers. He also places heavy value on how well a player peaked versus how he played over the long run (which gives the nod to a guy like Bill Walton over Robert Parish).

A few of the impressive qualities of the book is that he gives older players their due, such as Bob Pettit, Dolph Schayes, Bob Cousy, Sam Jones, George Mikan. He doesn't overlook their accomplishments and their contributions, going so far as to rate Pettit over every forward except Bird and Tim Duncan. In addition, while respect is given to the pioneers, youth is served, as players such as Kobe Bryant, Allen Iverson, Tracy McGrady, Tim Duncan, and Kevin Garnett are also featured.

Kalb convinced me to re-think a few of my own rankings. I still stick to my guns on Oscar Robertson being the greatest guard of all-time, but thanks to Kalb, I moved Bob Cousy ahead of Isiah Thomas and John Stockton among point guards, because he did dominate his era far more than the latter did in theirs. I have also reconsidered how I rate Rick Barry, Bill Walton, and a few other players.

As a breath of fresh air from most books and articles, he mentions things the mass media intentionally overlook: such as Karl Malone's big game chokes (he cites them one by one), Dennis Rodman's contribution to the 1996-98 Chicago Bulls; Michael Jordan's 3 consecutive losing seasons and his 1-9 playoff record before Scottie Pippen, and how Scottie Pippen put up his finest seasons in Jordan's absence. His statistical research is immense and impressive, listing such obscure stats as the oldest players to average 30 ppg, as well as the youngest.

Along with covering detailed statistical parts of their games, he will compare a given player to some contemporaries, asking people from a panel, so that you can get outside opinions. He also compares players to non-NBA contemporaries. Sometimes this works - Bill Russell and Joe DiMaggio was insightful - and sometimes it does not - Charles Barkley and Elvis was a bit cornball.

He also remembers things like Allen Iverson's incredible run in 2001 (whereas most writers forget the guy who finishes #2), and he takes into consideration how players didn't vote for Rick Barry due to personal dislikes, rather than on-court talent.

The big letdown comes with statistics. It's like jump shooting: you live by it and you die by it. They never tell the entire story. For instance, it is hard to gauge defense, before 1974, when blocks and steals were not recorded, and even when they were recorded, they never tell the entire story (Joe Dumars and Dennis Rodman didn't amass great totals in either category). With that in mind, it seems like when in doubt, offensive players were given more honor than defensive players, placing some questionable offensive-minded players to fill out the list, when the argument supporting them appears to fly in the face of his standards for comparing players. Let me expound.

While some defensive players got their due (Bill Russell #3, Dennis Rodman #30), there were some questionable people who got on the list who were lousy defensive players, or fair, at best, such as Pete Maravich (#47), Dominique Wilkins (#49), and Bob McAdoo (#44) while guys like Dave Debusschere and Nate Thurmond were left off. There is a chapter in the back explaining while some players were left off, but I thought the explanations were lacking. In all fairness, though, if every argument - pro and con - were carried out to the fullest detail, this would be an encyclopedia, instead of a book, and who is going to pay for a 50-volume set of books? But I will cite what I thought were a few inconsistencies:

Kalb argues that Nate Thurmond never won a title and never made first or second team All-NBA, which is true. However, Reggie Miller never did, either, and the All-NBA team only selects one center, but two guards. Both players played in the finals, but didn't win. These similarities should have disqualified Miller, but Miller's playoff heroics let us know that these standards are not the end-all/ be all. Therefore, consider that Thurmond made first team all-defense twice, which Miller never came close to achieving. Furthermore, if the award would have been given back then, he probably would have won defensive player of the year in 1971 (Kalb does offer "what if arguments, such as 'What if the three-point shot had existed when Maravich and Schayes played?') The two greatest offensive centers in history, Chamberlain and Jabbar, both have said that Thurmond was the toughest defensive center they played against. This gives him a credible argument for being the greatest defensive center in history or at least #2 (behind Bill Russell), and when you combine that with the 20.5 ppg, 22.0 rpg, and 4.2 apg he posted in 1968 (remember, Kalb prefers looking at a player at his peak rather than his longevity), I think he should be an obvious choice over guys who didn't play much defense and shot a lot. To me, putting guys like Maravich, Miller, McAdoo, and Wilkins, who only played on one end of the court, makes as much sense as putting Mark Eaton on the list. Maravich couldn't defend and never played for a competitor, and McAdoo nearly destroyed the Boston Celtics, before he did destroy the Detroit Pistons and was responsible for giving the Celtics the greatest frontcourt in history and forcing Dick Vitale from the NBA into his job as the most annoying man in the world. The only time he won a title was when he became a poor man's James Edwards- type of role player who scored about 10 ppg.

Another inconsistency is that only one MVP is not in the top 50: Wes Unseld. He is listed as the guy who just missed the list. However, all of the arguments that kept Thurmond off the list should have put Unseld on the list. He was MVP. He played in 3 finals, made All-NBA, and won a championship, which gave him more credentials than Wilkins and Miller.

The other problem with using stats is that stats never tell the story. They cannot measure attitude, desire, and hunger. Because of that, the book ignores the immeasurable metrics, creating a false list based on limited tools.

Another area for some improvement involved a small handful of outside opinions/analysis. For instance, asking Stephen A. Smith (who I hold in low regard) who is better between Oscar and Magic, he says Magic and adds "I'm only 35 years old, and I only remember seeing Magic". You can tell that he knows next to nothing about the Big O and that pretty much disqualifies him as a knowledgeable opinion. I'm slightly younger than he, but I've made it a point to research Robertson in order to make an informed opinion, as has Kalb. I think someone like Matt Guokas or Tommy Heinsoln would have better complimented the other two opinions listed in that comparison (Leonard Koppett and Nate Archibald). While I am not a Smith fan, he would be better suited to discuss Iverson versus Gary Payton. And while Boston Globe writer Bob Ryan makes many good points in the book, asking him to compare a Boston Celtic to any player is about as unbiased as asking the guys from Saturday Night Live to compare somebody to Mike Ditka ("Ditka versus Tiger Woods in a game of golf: Ditka!"). This is again nitpicking, as these instances were few and far between. I would have loved to see what everyone on the panel thought about each match-up, but again, that makes for a 50-volume set of books.

There is a small section in the back talking about some of the great teams: the best Russell team, the best Jordan team, as well as the best individual season. It wets the appetite to think about Kalb listing the greatest teams ever (how does the '67 Sixers stack up against the '73 Lakers, the '86 Celtics vs. the '87 Lakers, etc), or who the greatest defensive players are by position, who the greatest sixth men were, the greatest coaches, rookie seasons, etc. He's knowledgeable and interesting enough that you care what he thinks, even if you don't agree, which is a high compliment.

Overall, this book is an easy read. If you don't know your basketball history, this is an excellent way to hop on board and learn about it. If you do know your basketball history, this is your way to compare your opinions to another educated historian and learn a few things. The book is an incredibly fast read, with each player having about 6 pages devoted to him. You get a big of career biography, some statistical analysis (but not too much, which becomes as dull as some baseball books), comparisons to other players, and commentary. It is also a unique book. I have an entire library, but none of them have the audacity to devote the entire topic to comparing and listing the players of history. The book is extremely well written and the research behind it is some of the most thorough research ever put into a basketball book.

Introspection: N/A

Insight: 4

History: 1955-2003

Readability: 5

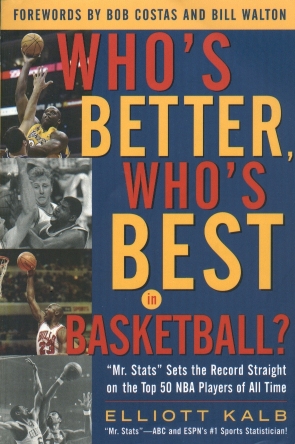

Who's better who's best in basketball?: Mr. Stats sets the record straight on the top 50 players of all-time. Elliott Kalb. Contemporary Books. 2004.